ASTRO SPACE NEWS

A DIVISION OF MID NORTH COAST ASTRONOMY (NSW)

(ASTRO) DAVE RENEKE

SPACE WRITER - MEDIA PERSONALITY - SCIENCE CORRESPONDENT ABC/COMMERCIAL RADIO - LECTURER - ASTRONOMY OUTREACH PROGRAMS - ASTRONOMY TOUR GUIDE - TELESCOPE SALES/SERVICE/LESSONS - MID NORTH COAST ASTRONOMY GROUP (Est. 2002) Enquiries: (02) 6585 2260 Mobile: 0400 636 363 Email: davereneke@gmail.com

NEW MODEL RELEASED: ZWO announced their new Seestar S30 Pro Smart Telescope a few months ago at the NEAF show in the USA SEESTAR WEBSITE: https://www.seestar.com/Your Australian retailer BINTEL:https://bintel.com.au

Astronomy Home Visits - We Come To You

Ask Yourself Have You Ever... Touched a real space rock? Seen the rings of Saturn? Viewed star clusters 17,000 light years away? Seen the craters and 'seas' on the Moon up close... or just looked through a large telescope? View Planets, Exploding Stars, Clusters - Take a Laser Guided Sky Tour Indigenous Sky Stories - Hold a Real Meteorite - Take Your Own Moon Photo - See a Real Piece of Moonrock. Kids Catered for.

With world renowned astronomer, lecturer and media personality Dave Reneke as your guide you'll view amazing planets, stars, clusters & constellations. David is an expert astronomy lecturer, writer, author and heard on over 50 radio stations across Australia each week! Designed for those with no knowledge of astronomy this talk is covered in simple, easy to understand terms. (Hastings NSW Only) Adults $25 Kids $10 (U12) Ph 0400 636 363 Email www.davereneke@gmal.com

Australia's Night of Fire: The Blood Moon of March 3–4, 2026

On a warm late-summer evening, as cicadas hum and the day's heat slowly drains from the streets of Sydney and the hills of regional New South Wales, the Moon will begin to change.

On the night of March 3–4, 2026, Australians will witness a total lunar eclipse — the kind often called a blood moon. For just under an hour, the Moon will glow in deep copper and red, suspended above the eastern and south-eastern sky. It is a rare, shared moment: the entire country, from Perth's beaches to Hobart's waterfront and out across the plains of western NSW, will be able to look up and see it.

When to Look Up

For readers in New South Wales — including Sydney — the key times (AEDT) are:

-

Partial eclipse begins: 8:50 pm

-

Totality begins (Moon fully in shadow): 10:04 pm

-

Maximum eclipse: 10:33 pm

-

Totality ends: 11:02 pm

The real drama unfolds between 10:04 pm and 11:02 pm, when the Moon turns fully red. Maximum colour arrives around 10:33 pm. Elsewhere in Australia, the timing shifts slightly westward with the time zones, but every state and territory will have a view. Even Perth, where the Moon will be low early on, will see totality from 7:04 pm, peaking at 7:33 pm AWST.

This eclipse is the second event in the first eclipse season of 2026. Later in the year, on August 27–28, Australians will see a partial lunar eclipse — but it won't match the drama of March's total event.

What Actually Happens

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Earth moves directly between the Sun and the Moon. The Earth casts a long shadow into space, and the Moon drifts into it. But why red?

Even when the Moon is fully inside Earth's shadow, it doesn't vanish. Sunlight bends as it passes through our atmosphere. The blue tones scatter away — which is why our sky is blue during the day — and the red and orange light continues on, curving into the shadow and gently lighting the Moon.

In a sense, every sunrise and sunset on Earth is projected onto the Moon at once. The exact shade depends on the state of our atmosphere. After major bushfire seasons or volcanic eruptions, the Moon can appear darker and deeper red. On clear, clean-air years, it may glow more orange or copper.

How It Will Feel

The shift is gradual at first. A dark bite appears on one edge of the Moon. Over the next hour, the shadow grows, sliding across the familiar face we know so well. Then, suddenly, it is no longer silver. It is ember.

In rural New South Wales — away from city lights — the transformation can feel almost theatrical. The stars grow sharper as the Moon dims. The landscape takes on a softer tone. It is not frightening, not dramatic in a thunderclap way — but quietly profound. You are watching celestial geometry unfold with absolute precision.

What Ancient People Thought

Long before we understood orbits and light scattering, a blood moon demanded explanation. Across many cultures, it was seen as a warning, a battle in the heavens, or a sign of great change. In some traditions, a celestial creature was believed to be devouring the Moon. People would make noise — drums, shouting, clanging metal — to scare it away.

Closer to home, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have rich sky traditions that link the Moon to law, life cycles, and relationships between Earth and sky. In several traditions, an eclipse represented the Sun and Moon coming together — a powerful and sometimes dangerous moment requiring respect.

Even today, standing beneath a red Moon, it's easy to understand why ancient observers felt awe. The Moon has always been constant. When it changes colour, something feels out of balance. Yet what makes this event so powerful is that it is both predictable and rare. We can calculate it to the minute — and still feel wonder.

How to See It at Its Best (NSW Focus)

You don't need a telescope. In fact, you don't need any equipment at all.

Here's how to make the most of it:

-

Face east to south-east. The Moon will be rising and climbing through that part of the sky during the evening.

-

Find a clear horizon. Head to the coast, a hilltop, or an open park away from tall buildings.

-

Escape city glare if possible. Western Sydney, regional NSW, the Blue Mountains, or the Central West will offer darker skies.

-

Arrive early. Watching the partial phase build makes totality more meaningful.

-

Bring binoculars. They reveal subtle shading and the curve of Earth's shadow.

-

No eye protection required. Unlike a solar eclipse, lunar eclipses are completely safe to watch.

For photographers: use a tripod, a zoom lens if you have one, and take a range of exposures — the Moon will be much dimmer during totality than you expect.

A Shared Australian Sky

One of the most beautiful aspects of this eclipse is that it unites the country. At 10:33 pm in Sydney, 9:33 pm in Brisbane, 9:03 pm in Darwin, and 7:33 pm in Perth, millions of Australians will be looking up at the same red Moon. From Bondi Beach to Broken Hill. From Canberra's Parliament lawns to the red soil outside Alice Springs.

In a time when so much feels divided and fast, a lunar eclipse slows everything down. It reminds us that we are on a turning Earth, moving through space together. On March 3–4, 2026, step outside. Let your eyes adjust. Watch the shadow rise. For less than an hour, the Moon will burn softly above New South Wales — not in danger, not in omen, but in quiet, beautiful alignment. And then, just as gently, it will return to silver.

UFOs Where Do They Come From? Barack Obama and 'The Interrupted Journey'

In the autumn of 1961, on a dark ribbon of highway near Lancaster, New Hampshire, two ordinary Americans drove into a mystery that would echo for generations. Now that mystery is heading to the screen. Barack Obama and Michelle Obama are producing a Netflix film about Betty and Barney Hill — the couple whose strange night in 1961 helped shape the modern alien abduction story. And the timing could not be more curious.

On September 19, 1961, the Hills were driving home to Portsmouth after a holiday in Canada. Betty, a social worker, spotted a bright light in the sky. At first it looked like a star. Then it moved. It changed direction. It seemed to follow them.

Barney, a postal worker and a cautious man, pulled over. Through binoculars, he later said he saw a structured craft with rows of windows. Inside, figures. Watching. They drove off in fear. Soon they heard rhythmic buzzing sounds. The car vibrated. Then — silence. When they arrived home, nearly two hours of their journey were missing.

Betty's dress was torn. Barney's shoes were scuffed. Their watches had stopped. Both felt deeply unsettled. In the weeks that followed, Betty reported vivid dreams of small beings with large eyes. She described medical examinations aboard a craft. Barney suffered anxiety and ulcers. In 1964, under hypnosis conducted by psychiatrist Dr. Benjamin Simon, both recounted similar stories of being taken aboard a non-human vehicle.

Simon believed their accounts were likely shaped by stress and Betty's dreams. Hypnosis, critics argue, can create false memories. There was no physical evidence. No landing marks. No debris. Nothing left behind but testimony. And yet the details were striking

This was 1961 — before alien abduction stories became common in popular culture. The Hills described small grey beings years before "grey aliens" became a cultural icon. Their case exploded after publication of The Interrupted Journey by John G. Fuller in 1966. The book became a bestseller. The idea of "missing time" entered the UFO vocabulary. A template was born.

Supporters still point to Betty's alleged star map. She claimed one of the beings showed her a map of stars. Years later, amateur investigator Marjorie Fish attempted to match it to the Zeta Reticuli star system. Was it coincidence? Pattern-seeking? Or something else? Astronomers remain sceptical. The map was vague. Interpretations varied. No hard proof followed.

But what if? What if two ordinary citizens really did encounter something unknown on that road? What if the Hills were ahead of a wave of experiences that would surface decades later? Or what if this was a powerful psychological event shaped by Cold War fears, racial tension, and the anxiety of being an interracial couple in early 1960s America — years before such marriages were nationally protected under law?

The Obamas' interest may lie as much in that social backdrop as in the sky above it. Barney was active in civil rights. The couple lived under constant strain. Fear can come from prejudice as easily as from the heavens. And now comes another layer of intrigue.

Donald Trump has repeatedly hinted that further information about UFOs — now officially termed Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAP) — may soon be revealed. During and after his presidency, Trump acknowledged being briefed on such matters. He has suggested that more disclosure could come. So far, no formal announcement has materialised. But speculation is rising.

Is it possible that significant information is being withheld? The U.S. government has already confirmed that some UAP incidents remain unexplained. Pentagon reports released in recent years acknowledge objects performing unusual manoeuvres without clear explanation. Yet "unexplained" does not mean extraterrestrial. It means insufficient data.

Still, the public imagination connects the dots.

An Obama-produced film revisits the most famous abduction case in history. Trump hints at disclosure. Congress holds hearings on unidentified objects. What if new documents surface? What if radar data, once classified, reveals something startling? Or what if, once again, the mystery remains just beyond reach?

The evidence in the Hill case remains entirely testimonial. No physical artefacts. No verified alien craft. But the impact is undeniable. Their story shaped books, films, television and an entire cultural mythology.

On a quiet road in 1961, two hours vanished. Whether that gap holds an extraterrestrial encounter or a deeply human story shaped by fear and memory is still debated. Now, as Hollywood turns its lens back to that lonely highway — and as political whispers of disclosure swirl — the question rises again. What really happened out there in the dark?

And if an announcement does come — will it confirm our wildest suspicions, or simply remind us how powerfully the unknown grips the human mind? The road is still there. The stars still shine above it. And the mystery refuses to fade.

Astronomers Witness a Star Vanish Into a Black Hole in the Andromeda Galaxy

Astronomers have long known that stars can die in spectacular ways, but a recent discovery has offered one of the most dramatic endings ever observed. For the first time, scientists have watched a distant star simply disappear—collapsing directly into a black hole without the usual explosive farewell. This rare cosmic event took place in our neighbouring Andromeda galaxy, about 2.5 million light‑years from Earth.

Most massive stars end their lives in a supernova, a brilliant explosion that can briefly outshine an entire galaxy. But not all stars follow this script. Some are thought to undergo a "failed supernova," where the star collapses under its own gravity and forms a black hole quietly, without the dramatic fireworks.

That's exactly what astronomers believe they have witnessed.

Over several years, telescopes monitoring Andromeda noticed that a once‑bright star gradually dimmed and then vanished completely. There was no explosion, no expanding cloud of debris—just a fading point of light that eventually winked out of existence. The only explanation that fits the data is that the star collapsed straight into a black hole.

Seeing a star collapse directly into a black hole is extremely rare. Until now, astronomers had only theories and indirect evidence. This observation provides a real‑world example of how some of the universe's most mysterious objects are born.

It also helps scientists understand how many black holes exist in galaxies like our own, how massive stars evolve in their final stages, and why some stars explode while others don't. Each of these questions plays a role in shaping our understanding of galaxies, star formation, and the life cycle of matter in the universe.

The Andromeda galaxy is the closest large galaxy to the Milky Way, making it an ideal target for long‑term observation. By watching stars there over many years, astronomers can catch rare events like this one—moments that would otherwise be lost in the vastness of space.

This disappearing star is a reminder that the universe is constantly changing, even if those changes unfold over millions of years. And every now and then, our telescopes catch something extraordinary.

Although the star's final moments were silent and invisible, the black hole it left behind will continue to shape its surroundings for billions of years. It may pull in nearby gas, influence the motion of neighbouring stars, or even merge with another black hole in the distant future.

For astronomers, this event is a milestone—a rare chance to witness the birth of one of the universe's most extreme objects. For the rest of us, it's a humbling reminder of how much there is still to discover beyond our own galaxy.

The Best Thing I Ever Saw In The Night Sky

I've been amateur astronomer for over 60 years; I speak on 50 stations across Australia weekly on Space and Astronomy issues and conduct yearly Astro Tours to Norfolk Island, sharing the sky with anyone willing to tilt their head back and wonder.

But if you ask me my favourite night-sky object, I won't say Saturn. I won't say the Orion Nebula. I won't even say the Moon. It's Sputnik.

October 4, 1957. About 7 pm. Cabramatta, NSW. A warm suburban evening. Back then the world felt smaller. No internet. No space stations. No one had walked on the Moon. In fact, most of us assumed space was something for Buck Rogers and comic books. Rockets belonged in science fiction. The idea that something man-made could orbit the Earth? That wasn't just unlikely — it was unthinkable.

Dad called me outside. There was a seriousness in his voice that made me look up before I even knew why. He pointed to a tiny light gliding steadily across the dark sky.

"That's Sputnik," he said.

Just a moving dot. No flashing lights. No dramatic music. But in that quiet backyard, history slid silently overhead. The first artificial satellite. The beginning of the Space Age. And I was standing there in short pants, probably with grass clippings stuck to my socks, staring at the future.

Something shifted in me that night. A switch flicked on. If humans could put that little metal ball into orbit, what else was possible? What was up there? How did it work? Who built it? I needed answers.

I practically devoured the school library's space section — which, to be honest, didn't take long. Then along came Patrick Moore. His books didn't just inform me; they electrified me. The sky was no longer a backdrop. It was a frontier. And I wanted in.

Nearly seventy years later, I'm still chasing that feeling. I've peered through countless telescopes, from modest backyard setups to impressive modern instruments. Today I use the Seestar S50, and what it reveals is breathtaking — galaxies millions of light-years away, glowing nebulae, star clusters that look like cosmic jewellery. It's astonishing what fits into a portable case these days.

And yet — here's the truth — nothing, absolutely nothing, has ever eclipsed that first sight of Sputnik drifting over Cabramatta. No high-resolution image. No cutting-edge technology. No dazzling deep-sky object. That tiny moving light did more than circle the Earth. It circled my imagination and never let go.

Back then, the world felt grounded. Suddenly, it wasn't. The sky was no longer the limit — it was the beginning. None of us kids in the backyard knew we were witnessing the dawn of a new era. We just knew something extraordinary was happening.

These days, when I'm on air or guiding a group under the Norfolk Island stars, I sometimes glance at a young face in the crowd — eyes wide, questions forming — and I recognise that look. I've seen it before. I wore it.

Somewhere out there tonight, a child is standing in a backyard, staring upward at something small and moving, feeling that quiet spark ignite. It might not be Sputnik this time. But it will be their moment.

A City on the Moon: Why SpaceX Shifted Its Focus

For years, Mars was the promised land — the red beacon in the night sky, close enough to tempt us yet distant enough to demand courage. Elon Musk spoke openly of sending a million people there. SpaceX built rockets designed to make that ambition technically possible. The plan was bold but straightforward in theory: perfect Starship, refuel it in orbit, launch fleets during favorable windows, and begin building a permanent human settlement on Mars.

For a decade, Mars was the headline.

In early 2026, however, SpaceX recalibrated its near-term priorities. Rather than pushing immediately toward a Martian colony, the company shifted its operational focus to establishing a sustained human presence on the Moon. This was not a retreat from Mars, but a strategic sequencing of objectives.

The reasoning is practical. The Moon is roughly three days from Earth; Mars, depending on orbital positions, requires a journey of six to nine months. If a life-support system fails on the Moon, assistance can arrive within days. If a critical system fails en route to Mars or on its surface, crews must endure months of isolation before help is even theoretically possible. Proximity changes risk calculations dramatically.

Engineering considerations also favor the Moon as a first build site. It offers no atmosphere to cushion landings, endures temperature swings from extreme heat to deep cold, and is coated in abrasive dust that infiltrates machinery and seals. These harsh conditions force engineers to solve many of the core challenges of off-world living. Crucially, solutions can be tested and refined quickly. Hardware can be upgraded within a single launch cycle, and lessons learned can be applied within months rather than years. By contrast, Mars missions are constrained by launch windows that open roughly every 26 months, limiting the pace of iteration.

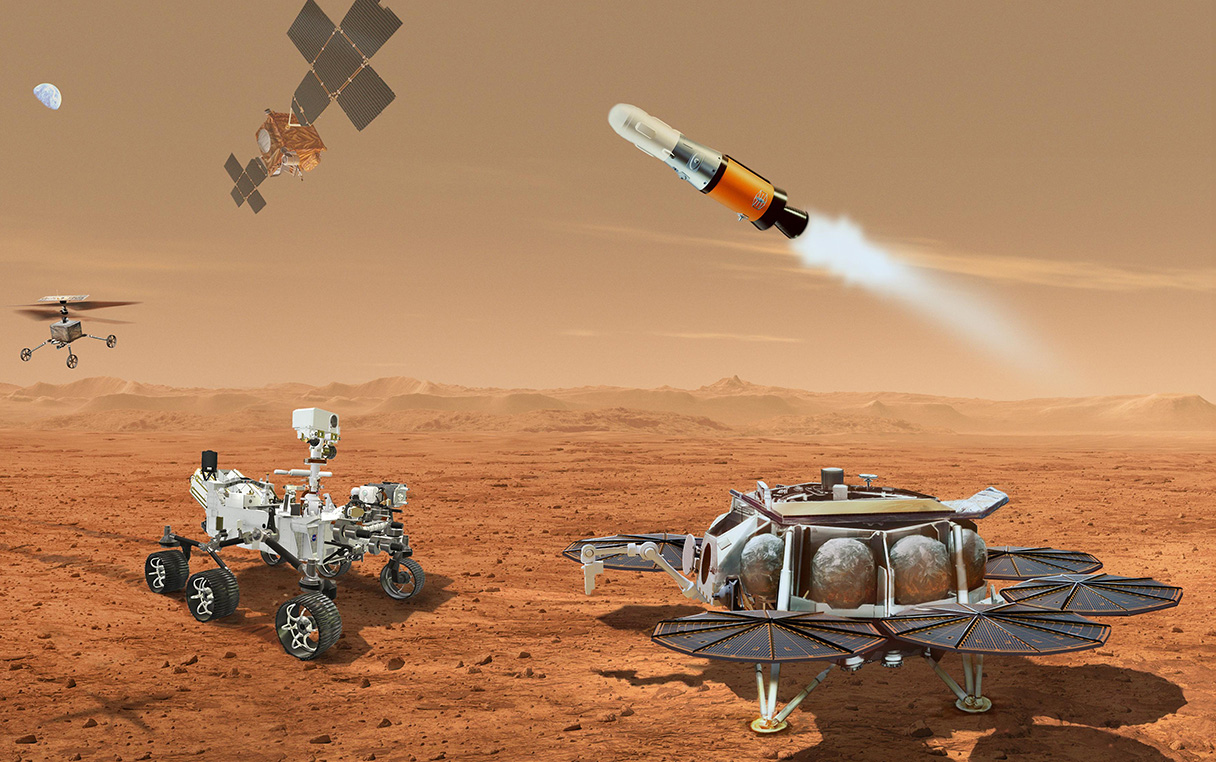

Policy and funding have also influenced the shift. NASA's renewed commitment to lunar exploration through the Artemis program placed the Moon at the center of U.S. space strategy. Artemis aims to return astronauts to the lunar surface and establish a sustained presence there. SpaceX's Starship was selected as the Human Landing System for these missions, directing substantial company resources toward lunar-specific engineering, including landing systems, life-support adaptations, and surface operations planning.

Where government priorities lead, contracts follow. Mars remains a long-term aspiration, but the Moon currently carries funded programs, defined timelines, and international collaboration. Nations that may lack the capacity for independent Mars missions can realistically contribute to lunar infrastructure — communications, robotic prospecting, surface habitats and logistics. In this sense, a lunar city becomes a multinational enterprise, while Mars remains, for now, largely a privately driven ambition.

Scientific discoveries have further strengthened the Moon's appeal. Observations over the past two decades confirmed significant deposits of water ice in permanently shadowed craters near the lunar south pole. Water is indispensable for human survival, but it also has strategic value. When separated into hydrogen and oxygen, it becomes rocket propellant. A settlement capable of producing fuel locally would transform space logistics, potentially turning the Moon into a refueling hub for missions deeper into the solar system — including Mars.

In-situ resource utilization, the practice of using local materials, is central to this vision. Lunar regolith can be processed into construction materials, radiation shielding and oxygen. The ability to manufacture essential supplies on site reduces the mass that must be launched from Earth, lowering costs and increasing sustainability. Building a city becomes more feasible when the surface itself provides raw materials.

None of this implies that Mars has been abandoned. The long-term objective of establishing a self-sustaining civilization beyond Earth remains central to SpaceX's stated mission. Mars offers advantages the Moon cannot: a near-24-hour day, abundant carbon dioxide for fuel production, and vast terrain suitable for expansion. Its environment, while harsh, may ultimately be more conducive to large-scale settlement than the Moon's airless landscape.

Yet the Moon offers immediacy. It allows technology to mature, operational experience to accumulate, and economic models to develop in cis-lunar space. Commercial services — communications networks, navigation support, research platforms and cargo delivery — can begin generating revenue well before a Martian economy exists.

In effect, the Moon represents an apprenticeship. By mastering sustained operations just beyond Earth, humanity builds the technical, financial and psychological resilience required for deeper ventures.

Exploration has rarely progressed in a straight line. Coastal voyages preceded ocean crossings; nearby islands were settled before distant continents. In that historical pattern, the Moon becomes less a stepping stone and more a proving ground.

Mars remains the long horizon — red, distant and compelling. But before humanity attempts to build a city millions of kilometers away, it may first construct one in Earth's immediate neighborhood, learn from it, and carry those lessons outward. The shift is not a surrender of ambition. It is a reordering of steps — one that may ultimately make the journey to Mars more achievable than ever.

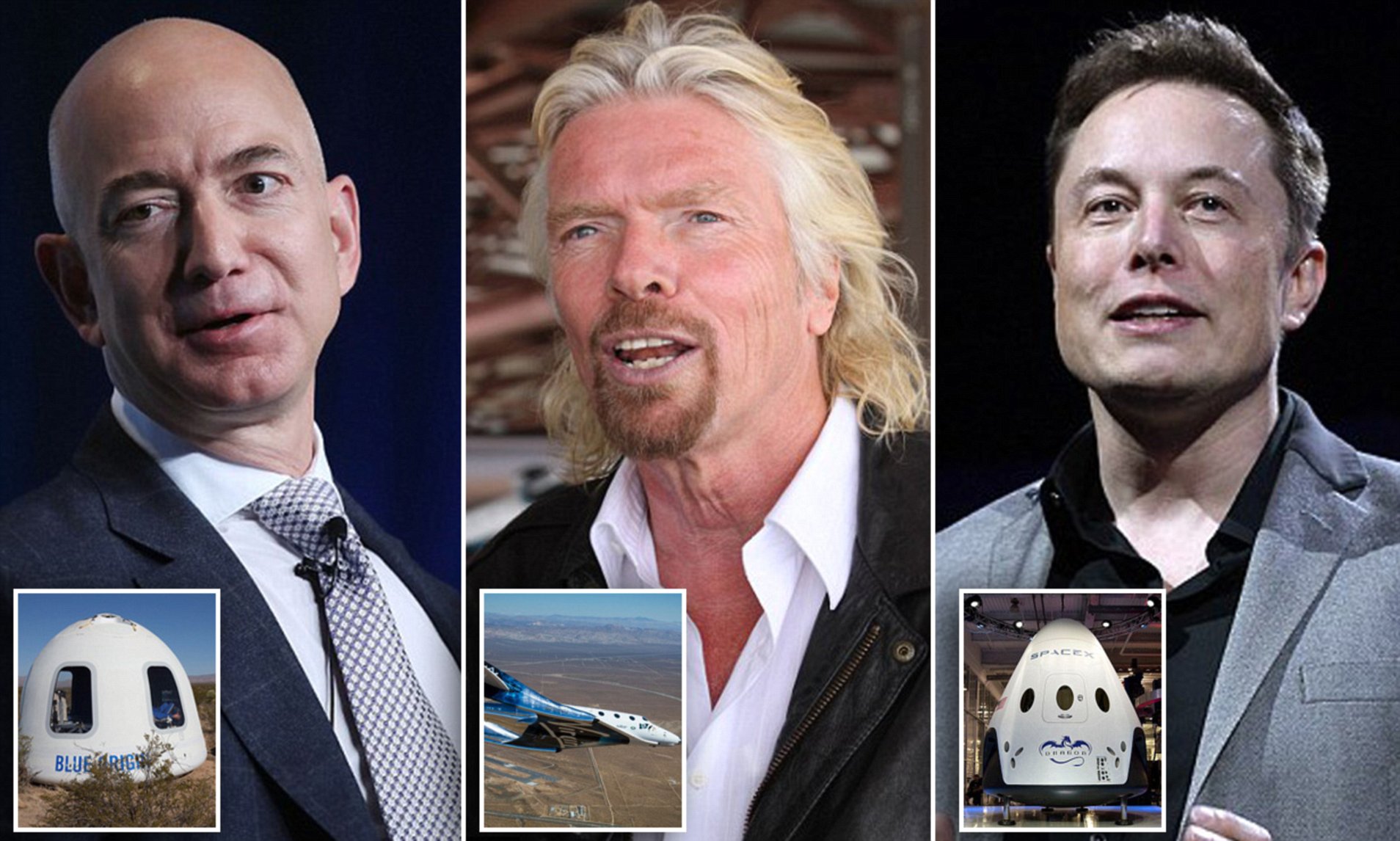

The Race To The Moon Is Now a Billionaire Showdown — And It's Heating Up Fast.

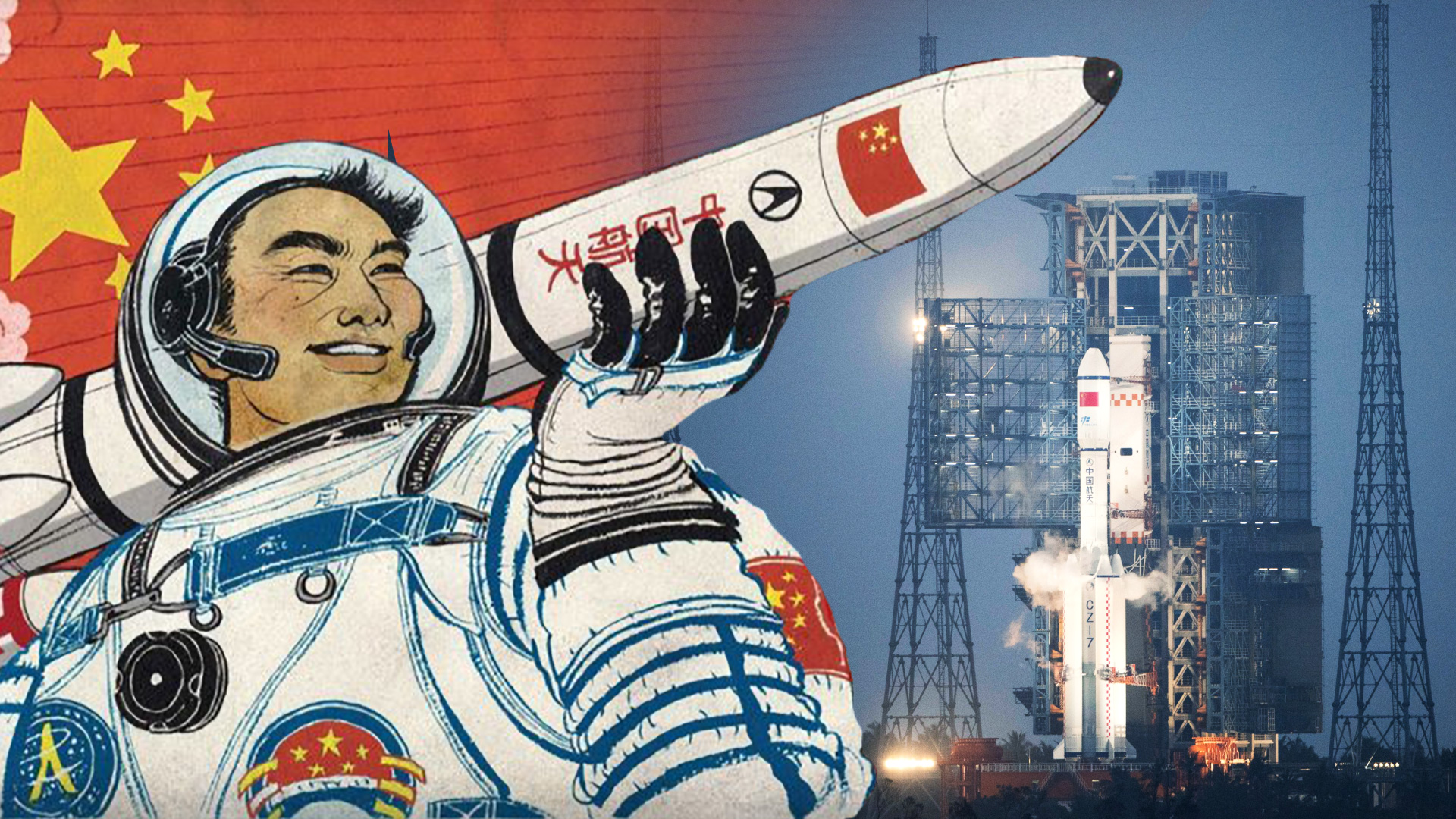

Two of the world's richest men are now locked in a serious battle over who will help take humans back to the lunar surface. On one side is SpaceX, led by Elon Musk. On the other is Blue Origin, founded by Jeff Bezos.This isn't just about bragging rights. It's about contracts, technology, and control over the next big step in space.

NASA wants to send astronauts back to the Moon under its Artemis program. Instead of building everything itself, the agency is paying private companies to do it. SpaceX won the first major contract to build the lunar lander — the spacecraft that will actually carry astronauts from orbit down to the Moon's surface.

That was a huge win. It put Musk's giant Starship rocket right at the heart of America's return to the Moon. Blue Origin wasn't happy. The company pushed back and argued the contract should not go to just one provider. In time, NASA agreed to support a second lander — giving Blue Origin its own shot at putting astronauts on the Moon.

Now the race is very real. SpaceX is known for moving fast and taking big risks. Its new Starship rocket is huge and designed to be reused again and again. The idea is simple: lower costs and carry more cargo than ever before.

Blue Origin is taking a steadier path. Its lunar lander, called Blue Moon, is aimed at delivering astronauts and equipment to the Moon's south pole — a region believed to hold frozen water. That water could be turned into fuel and drinking supplies. In other words, it could help humans stay on the Moon, not just visit.

That's the key difference. This is no longer about planting flags. It's about building a long-term presence. The U.S. government also has another reason to keep this competition alive. China is working toward its own lunar missions. Having two American companies building landers gives NASA backup options and keeps the pressure on.

So what began as private space dreams has become something much bigger. The Moon is once again a prize — not for national pride alone, but for future industry and exploration. The rockets are being built. The contracts are signed. And two billionaires are now racing to prove they can deliver. The Moon is waiting — and this time, the competition is fierce.

Life on Earth is lucky: A rare chemical fluke may have made our planet habitable

Life has a habit of making survival look easy. Oceans shimmer, forests breathe, clouds gather and fall. From a distance — say, a million miles out — Earth appears serenely alive, a blue-and-white world bathed in sunlight. In July 2015, the Deep Space Climate Observatory, better known as DSCOVR, captured its first full-disk image of the sunlit Earth from the L1 point between our planet and the Sun. The photograph was calm, almost casual in its beauty.

But beneath that calm surface lies a razor-thin margin of chemical fortune.

A recent study led by Craig Walton of ETH Zurich suggests that Earth's ability to host life may depend on an extraordinarily precise chemical balance during its earliest formation. Specifically, it comes down to oxygen — not the oxygen we breathe today, but the oxygen present when Earth was still molten and differentiating into core, mantle and crust. Too much or too little at that critical stage, and two essential elements for life — phosphorus and nitrogen — would have been lost to the planet's depths.

The result? A world that might look habitable from orbit but would be chemically sterile.

To understand this, we need to wind the clock back 4.5 billion years. The young Earth was a violent place: a growing sphere of rock repeatedly struck by planetesimals, heated by radioactive decay and gravitational compression. As it melted, heavy metals such as iron sank inward to form the core in a process known as differentiation. Lighter materials rose toward the surface, forming the mantle and eventually the crust.

This internal sorting was not just a structural event. It was a chemical one.

Phosphorus and nitrogen — both vital to life — behave differently depending on the oxygen conditions present during core formation. If oxygen levels are too low, these elements tend to bond with iron and become locked inside the core. Once there, they are effectively removed from the surface environment where life might use them. If oxygen levels are too high, other chemical pathways can sequester them in ways that also make them unavailable for biology.

Walton and colleagues argue that Earth formed in a narrow "Goldilocks" window of oxygen availability. Under those conditions, enough phosphorus and nitrogen remained in the mantle and crust rather than disappearing into the core. That retention allowed later geological processes — volcanic outgassing, weathering, hydrothermal circulation — to cycle these elements into the oceans and atmosphere.

Phosphorus is fundamental to energy transfer in living cells. It forms the backbone of DNA and RNA and is central to ATP, the molecule that powers cellular activity. Nitrogen is equally indispensable. It is a core ingredient in amino acids, proteins and nucleic acids. Remove either element from the accessible surface reservoir, and life as we know it cannot assemble its molecular toolkit.

What makes this finding sobering is that surface habitability can be deceptive. Astronomers often assess distant exoplanets by looking for liquid water, temperate climates and suitable atmospheres. These are essential factors, but they may not be sufficient. A rocky planet could sit comfortably in its star's habitable zone, possess oceans and even maintain a stable atmosphere — yet lack the accessible phosphorus and nitrogen needed to build biology.

In other words, a planet might look like Earth from afar and still be fundamentally lifeless.

"Earth To Moon... Don't Forget To Phone Home."

Once upon a time, going to the Moon meant leaving everything behind. No wallets. No watches you trusted. No comforts. No distractions. And certainly—absolutely, categorically—no phones. Now NASA astronauts are heading back to the Moon with smartphones in their pockets.

Let that sink in. The same device you drop between the car seat and the console. The same one that buzzes with spam calls, weather alerts, and messages that begin with "Just circling back…" is now officially cleared for lunar travel. The Moon—once the domain of slide rules, checklists, and stoic men with nerves of steel—has finally gone mobile. This is either progress, madness, or the most human thing imaginable.

Back in 1969, Apollo astronauts flew to the Moon guided by a computer with less processing power than a modern digital wristwatch. Mission Control filled entire rooms with hardware to do calculations your phone now performs while playing music and updating your calendar. The Moon landing was an exercise in precision, discipline, and deliberate focus. Nothing unnecessary came along for the ride.

Fast-forward to today and NASA's Artemis astronauts can slip a smartphone into their flight kit—sealed, hardened, stripped of distractions, and loaded with apps for navigation, procedures, imaging, and emergency reference. It won't be doom-scrolling TikTok or posting lunar selfies to Instagram (sorry). But still: a phone. On the Moon. That's astonishing.

It's also deeply symbolic. The smartphone has quietly become the most powerful personal tool ever created. Camera, map, library, notebook, calculator, compass, communicator—it's the Swiss Army knife of the modern age. Of course it's going to space. It was only a matter of time before NASA looked at it and said, "Fine. You're coming."

What's deliciously ironic is that this humble rectangle now serves as backup to some of the most advanced spacecraft ever built. Redundancy is everything in spaceflight, and smartphones—ruggedised, locked down, and purpose-built—are reliable enough to earn a seat on humanity's return to the lunar surface. Not as toys. Not as comforts. As tools. There's something wonderfully grounding about that.

For decades, space travel felt distant and abstract. Astronauts were gods in helmets, floating above us in silence. But a phone in the pocket collapses that distance. It reminds us that the people walking on the Moon will still be human—checking notes, reviewing procedures, snapping reference photos, maybe feeling the faint phantom vibration of a notification that never comes.And maybe that's the real leap forward.

The Moon is no longer just a destination for flags and footprints. It's becoming a workplace. A research site. A staging ground. Bringing phones along is a quiet admission that space is shifting from the extraordinary to the operational. The impossible is becoming routine. The unthinkable is now standard issue.

Of course, it also raises one irresistible thought: somewhere in the future, an astronaut may look up from the lunar surface, glance at Earth hanging in the black sky, and pull a phone from their pocket—not to call home, not to scroll, not to post—but simply because that's what humans do. We carry our tools with us. Wherever we go.

From caves to cities. From oceans to orbit. And now, apparently, to the Moon. One giant leap for mankind. And one small device, vibrating silently in a spacesuit pocket, reminding us how far we've come—and how casually amazing it all is.

NASA has announced plans to establish a permanent human village on the Moon by 2035

This is marking a major shift in the agency's approach to lunar exploration. The announcement was made by NASA's Acting Administrator Sean Duffy while addressing the International Aeronautical Congress in Sydney, where he outlined a long-term vision that moves beyond short exploratory missions toward sustained human presence on the lunar surface.

According to Duffy, the proposed lunar village would support ongoing scientific research, technology testing, and international cooperation, while also serving as a critical stepping stone for future missions deeper into the solar system, including crewed journeys to Mars. The initiative represents the most ambitious phase yet of NASA's Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the Moon for the first time since the Apollo era.

The roadmap toward permanent lunar habitation begins with Artemis II, a crewed mission scheduled to launch within the next two years. Artemis II will send four astronauts on a 10-day journey around the Moon without landing, allowing NASA to fully test its deep-space systems, including the Space Launch System rocket and the Orion spacecraft. This mission will mark humanity's first crewed venture beyond low Earth orbit in more than five decades and is intended to validate life-support systems, navigation, and operational procedures required for future surface missions.

That mission will be followed by Artemis III, currently targeted for 2027, which is expected to return astronauts to the Moon's surface for the first time in over 50 years. During Artemis III, two astronauts will land near the Moon's South Pole and remain on the surface for approximately seven days. The landing will be conducted using SpaceX's Starship spacecraft, which NASA has selected as its human landing system. The South Pole region has been chosen because it contains areas of near-constant sunlight and is believed to hold water ice deposits, resources that could be essential for sustaining long-term human activity on the Moon.

Unlike the brief Apollo missions of the late 1960s and early 1970s, NASA's current objective is not symbolic achievement but permanence. The agency envisions a gradual buildup of infrastructure on and around the Moon throughout the late 2020s and early 2030s. This would include repeated crewed landings, expanded surface operations, power systems, habitats, mobility platforms, and scientific facilities, all designed to support longer stays and more complex missions. A lunar space station known as the Gateway is also expected to play a role by serving as a staging point in lunar orbit for surface expeditions.

NASA says a permanent presence on the Moon would deliver significant scientific and strategic benefits. Long-term habitation would allow researchers to study the Moon's geology and history in far greater depth, while also testing technologies needed to survive and work in deep space. Access to potential lunar resources, such as water ice, could reduce reliance on supplies from Earth by enabling the production of drinking water, oxygen, and even rocket fuel. These capabilities are viewed as essential for making future crewed missions to Mars feasible.

The lunar village concept is also intended to strengthen international and commercial partnerships. NASA has emphasized collaboration with allied space agencies and private companies as a core part of the Artemis program, positioning the Moon as a shared platform for peaceful exploration and innovation.

Despite the ambitious timeline, the project faces significant challenges. Technical hurdles, budget pressures, and delays in spacecraft development have already affected Artemis mission schedules, and building durable infrastructure in the Moon's harsh environment will require major advances in radiation shielding, energy generation, and surface construction. Nevertheless, NASA officials maintain that steady progress through the Artemis missions will lay the groundwork for achieving a sustained human presence on the Moon by 2035.

If successful, the lunar village would represent a historic milestone, transforming the Moon from a destination for brief visits into humanity's first permanent outpost beyond Earth and opening the door to a new era of space exploration.

US targets 500kW Moon nuclear reactor by 2030; aims to power future space missions

Life on Earth may owe its existence to something far less romantic than destiny and far more fragile than we like to admit: chemistry behaving itself at exactly the right moment.

We often talk about the "Goldilocks zone" — not too hot, not too cold — as if temperature alone signed off on life's lease. But habitability is not just about warmth and water. It's about chemistry. And in Earth's case, that chemistry may have balanced on a knife's edge.

Two of life's most essential ingredients are phosphorus and nitrogen. They don't get the glamour of oxygen or carbon, but without them, biology shuts down before it starts. Phosphorus is central to DNA and RNA — the very instructions of life. It forms part of ATP, the molecule cells use to store and move energy. Nitrogen is woven into amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. No phosphorus. No nitrogen. No cells. No life.

Here's the catch: both elements are sensitive to oxygen levels in ways that can make them disappear from the environment.

In Earth's early history, the atmosphere and oceans contained very little free oxygen. This was long before forests, before fish, before anything with lungs. Microbes dominated. Then came a profound turning point — the Great Oxidation Event around 2.4 billion years ago — when oxygen began building up in the atmosphere, largely thanks to photosynthetic microbes.

Oxygen is reactive. That's its job. It binds easily with other elements, altering their chemical state. In oceans with too much oxygen, phosphorus tends to become locked into insoluble minerals and sinks into sediments, effectively removed from circulation. Nitrogen, meanwhile, can be converted by microbes into nitrogen gas and lost back to the atmosphere in a process known as denitrification. Too little oxygen creates other problems — toxic conditions, unstable chemistry, limited energy pathways for life.

In short, life depends on a delicate oxygen middle ground.

If oxygen levels rise too high too quickly, phosphorus can be trapped in ocean sediments and become biologically unavailable. If oxygen drops too low, nitrogen cycling becomes unstable. Either extreme can choke off the nutrients that sustain ecosystems. The balance must be just right — not merely globally, but within oceans, sediments, and shallow coastal environments where early complex life evolved.

Geological evidence suggests Earth hovered in that middle zone for vast stretches of time. Oxygen levels rose slowly, plateaued, dipped, and climbed again in pulses. That gradual climb may have prevented catastrophic nutrient loss. It allowed phosphorus to remain mobile enough to support biological productivity, while nitrogen continued cycling in a form life could use.

In other words, Earth may have avoided chemical extremes by sheer good fortune.

Consider how easily this could have gone wrong. A slightly more vigorous volcanic outgassing phase. A different rate of continental growth. More rapid burial of organic carbon. Each of these factors influences atmospheric oxygen. Shift the dial too far and you alter nutrient cycles on a planetary scale.

Mars, for example, once had liquid water, river channels, and possibly habitable conditions. But without long-term atmospheric stability and active plate tectonics recycling nutrients and gases, its chemistry drifted into sterility. Venus took another path entirely — runaway greenhouse heating and surface conditions hostile to complex chemistry.

Earth's story appears to hinge on feedback loops that kept oxygen neither vanishingly scarce nor overwhelmingly abundant for long stretches of deep time. Oceans breathed just enough. Microbes adapted. Nutrient cycles stabilized. Complexity crept forward.

By the time multicellular life blossomed in the Cambrian explosion around 540 million years ago, the groundwork had been laid by billions of years of chemical negotiation.

What makes this unsettling — and fascinating — is the implication for life elsewhere. When astronomers scan distant worlds for oxygen in their atmospheres, they often treat it as a hopeful sign. But oxygen alone is not a guarantee of habitability. Too much can be as problematic as too little. The true prize may be planets where oxygen, phosphorus, and nitrogen cycles are locked in a stable dance.

Life on Earth did not simply appear because conditions were comfortable. It emerged because planetary chemistry threaded a narrow needle over immense spans of time. A rare chemical fluke? Perhaps.

Or perhaps the universe is filled with planets that almost made it — worlds where water flowed and volcanoes rumbled, but oxygen tipped the scales too far and phosphorus sank quietly into rock, leaving oceans biologically empty.

We exist because Earth's chemistry didn't overreact.

That's not destiny. That's balance — improbably sustained, exquisitely timed, and still unfolding beneath our feet.

The Most Distant Galaxy Yet — And It Defies Expectations

Just a few days ago, astronomers announced a groundbreaking discovery using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): a galaxy farther away than any previously observed. Named MoM-z14, its light has travelled more than 13.5 billion years to reach Earth, offering an extraordinary glimpse into the universe when it was just a fraction of its current age.

What makes MoM-z14 especially surprising is not just its distance, but its characteristics. The galaxy is brighter, more compact, and more chemically mature than scientists predicted for such an early epoch, with higher levels of nitrogen than expected. This challenges long-standing models of how galaxies form and evolve in the universe's first few hundred million years.

What this tells us: Discoveries like MoM-z14 are rewriting our understanding of cosmic history. They suggest that galaxy formation may have begun earlier and more rapidly than previously thought — and that the early universe may be stranger and more dynamic than scientists imagined.

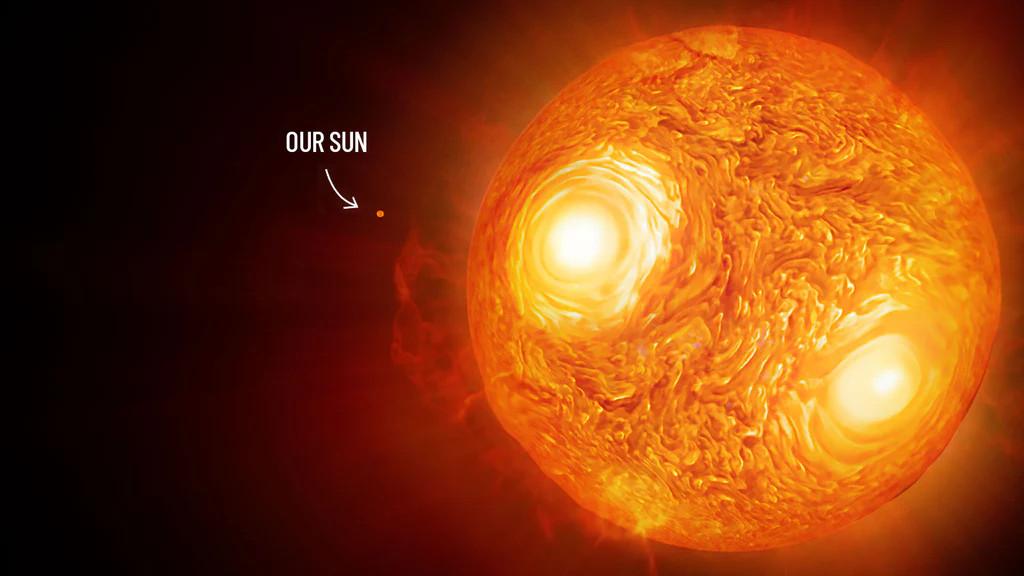

The Largest Star In The Universe. – A MONSTER

In the vast expanse of the cosmos, where the boundaries of the known and the unknown converge, a celestial enigma looms large, captivating the imagination of astronomers and the public alike. This enigma is none other than UY Scuti, one of the largest stars ever observed in the observable universe. As the night sky unfolds its celestial tapestry, the sheer scale of UY Scuti becomes increasingly apparent. Dwarfing our own sun by an astonishing factor of 1,700, this behemoth of a star would easily engulf the orbits of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars if placed at the center of our solar system. Imagine, for a moment, the awe-inspiring sight of a star so colossal that it could swallow our home planet whole, with room to spare.

To truly grasp the immensity of UY Scuti, one must consider its staggering dimensions. If you were to embark on a journey around the star's circumference, you would need to travel a distance of nearly 5 billion kilometres – a journey that would take you over 1,100 years to complete, even at the breakneck speed of a spacecraft. This is a scale that defies our everyday comprehension, a testament to the sheer vastness of the universe.

But UY Scuti's grandeur is not without its perils. This celestial giant is a variable star, meaning its brightness fluctuates over time, a testament to its inherent instability. Astronomers have observed that the star's diameter can vary by as much as 20% over the course of its pulsation cycle, a phenomenon that adds an element of suspense and intrigue to its study.

Beneath the surface of this colossal star lies a power that is truly awe-inspiring. UY Scuti is estimated to be emitting an astonishing 380,000 times the energy of our sun, a staggering amount of power that could potentially overwhelm and destroy any nearby celestial bodies. The mere thought of such raw, unbridled energy is enough to instil a sense of fear and reverence in the hearts of those who gaze upon it.

Yet, despite its immense size and power, the future of UY Scuti remains shrouded in uncertainty. As a red supergiant, the star is nearing the end of its life cycle, and its eventual fate is a subject of intense speculation among astronomers. Will it explode in a cataclysmic supernova, or will it slowly fade into obscurity?

The suspense surrounding this celestial enigma only adds to its allure, drawing scientists and the public alike to unravel the mysteries of this colossal star. As we gaze upon the night sky, let us be humbled by the sheer scale and power of UY Scuti, a testament to the grandeur and complexity of the universe we inhabit. For in the face of such cosmic wonders, we are reminded of our own insignificance, and the profound mysteries that still await us in the vast expanse of the unknown.

SpaceX files plans for million-satellite orbital data center constellation

SpaceX's Boldest Idea Yet: SpaceX has quietly floated one of the most ambitious space infrastructure ideas ever proposed: turning low Earth orbit into a vast, solar-powered data centre. In a recent regulatory filing, the company outlined plans for an orbital computing network made up of as many as one million satellites. If approved, it would dwarf every satellite constellation seriously considered so far and signal a radical shift in how and where the world's digital brainpower is housed.

The proposal envisions satellites operating between 500 and 2,000 kilometres above Earth, spread across carefully chosen orbital paths. Some would follow sun-synchronous orbits, remaining in sunlight almost constantly, while others would circle at lower inclinations to handle spikes in computing demand. The goal is simple but audacious: continuous access to solar power, without the land, cooling, and energy constraints that increasingly plague terrestrial data centres.

SpaceX argues that space offers a unique advantage. Above the atmosphere, solar energy is abundant and uninterrupted. With minimal maintenance and no weather, computing hardware could run more efficiently and with a smaller environmental footprint than facilities on the ground. As global demand for artificial intelligence computing explodes, the company believes orbit may soon become the cheapest place to generate large-scale AI processing power.

The scale of the proposal is unprecedented. Even the largest international filings to date—such as China's plans for nearly 200,000 satellites—are modest by comparison. SpaceX says it would place its satellites in largely unused orbital altitudes, although the filing offers few details about satellite size, mass, or final configuration.

Communication within the system would rely heavily on laser links between satellites, a technology SpaceX already uses in its Starlink network. Data would hop across the constellation in space before being sent to the ground through Starlink relay satellites. Traditional radio communications in the Ka-band would be used mainly as a backup for command and control.

Notably, SpaceX has not committed to a deployment schedule or cost estimate. It has also requested relief from standard regulatory milestones that normally require large constellations to be deployed within fixed timeframes. The company argues those rules are designed to prevent spectrum hoarding and are unnecessary in this case, as its backup radio usage would not interfere with other operators.

The idea of orbital data centres is gaining attention well beyond SpaceX. Rising electricity costs, water shortages, and community resistance are making large Earth-based data centres harder to build. At the same time, launch costs continue to fall. SpaceX believes these trends may soon tip the balance in favour of space-based computing.

The company plans to rely heavily on its Starship launch vehicle, designed to deliver unprecedented amounts of mass to orbit. In theory, this would allow entire generations of computing hardware to be deployed quickly and at scale. SpaceX even suggests that space-based AI processing could one day rival—or exceed—the total electricity consumption of the United States, without placing further strain on Earth's power grids.

Framed this way, the proposal is more than a technical filing. It is a statement of intent: a vision of space not just as a place for exploration or communications, but as critical infrastructure for the digital age. Whether the idea proves practical, economical, or politically acceptable remains to be seen. But if nothing else, it underlines how quickly the boundary between spaceflight and everyday life is disappearing—quietly, one satellite at a time.

Does God Have an Address in the Universe?

It's one of humanity's oldest questions, usually whispered beneath the stars: if God exists… where is God? Not who. Not why. But where. For most of history, that question lived safely in theology. Heaven was "above," hell was "below," and the rest was mystery. Then science arrived, armed with telescopes, equations, and an awkward habit of measuring things once thought unmeasurable.

Now comes a claim that sounds more like science fiction than physics. A Harvard-trained physicist has suggested that God may not only exist, but may even have a location within the universe.

Dr Michael Guillén—physicist, mathematician, and former science editor for ABC News—argues that if God exists outside space and time, physics may still hint at where that boundary lies. This is not religious doctrine, nor accepted scientific consensus. Guillén frames it clearly as a thought experiment, not a proof.

According to his reasoning, that "location" would be roughly 439 billion trillion kilometres away, or about 273 billion trillion miles from Earth. The number is almost meaningless in everyday terms.

Light itself, racing along at 300,000 kilometres per second, would take more than 46 billion years to cross that distance—over three times the estimated age of the universe. This is not somewhere among the stars. It lies far beyond the observable universe.

That detail matters. Modern cosmology tells us there is a limit to what we can see—a cosmic horizon beyond which light has not had time to reach us since the Big Bang. Space almost certainly continues beyond that horizon, but it is forever disconnected from us. Physics, as we know it, can describe no further.

Guillén's idea sits precisely at that edge. If God is the ultimate cause of the universe—existing outside space, time, and matter—then God would logically exist beyond the boundary of the observable cosmos. Not hidden in a galaxy or drifting in a nebula, but existing where physical reality itself breaks down.

This is not proof, and Guillén is explicit about that. Telescopes cannot detect God. Equations cannot isolate God. Physics can only describe where the universe ends and admit it cannot describe what lies beyond. That admission alone is striking. Science has shown that space and time themselves had a beginning. They are not eternal. They came into existence. That discovery shocked physicists in the 20th century and reopened a question science cannot answer on its own: what caused it all?

Guillén does not claim to answer that question. He simply places a marker at the limit of physics and says that if God exists, this is where physics would expect God not to be constrained by the universe it describes. Critics respond quickly. Some argue that assigning distance to a non-physical being is meaningless. Others note that the universe may be infinite, making any numerical boundary arbitrary. And none of Guillén's ideas are experimentally testable.

All of that is fair. But perhaps proof is not the point. Perhaps the point is that modern science has led us back to the same place ancient stargazers once stood—confronting a universe so vast that certainty gives way to awe. Whether one believes in God, doubts God, or rejects the idea entirely, Guillén's argument forces an uncomfortable thought. The universe appears structured in a way that leaves room—mathematically and philosophically—for something beyond it.

Not as a gap for ignorance to hide in, but as a boundary of knowledge itself. Science is astonishingly powerful. It has measured the age of the universe, weighed galaxies, and traced cosmic history back to its earliest moments. Yet it openly admits there is a horizon it cannot cross. And beyond that horizon, physics falls silent.

Whether what lies there is God, mystery, or simply the unknown may say more about us than the universe. But the idea that the cosmos might be pointing not to an answer, but to a limit, is unsettling in the best possible way. Perhaps the strangest thought is not that God might have a location. It's that the universe might be vast enough to keep the question alive.

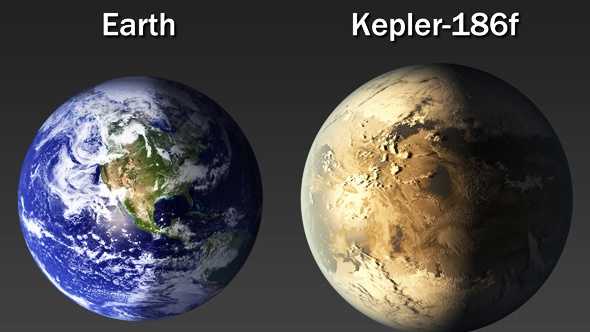

University of Southern Queensland astronomer discovers 'potentially habitable' planet candidate

Somewhere 150 light-years from Earth, a world may be waiting — an Earth-sized planet circling a star much like our own Sun. Astronomers from the University of Southern Queensland, in collaboration with Harvard and Oxford, have announced the tantalising discovery of Planet HD 137010 b, a candidate that could bring us closer than ever to finding another Earth.

It's small, just six percent larger than our planet, but its significance is enormous. The planet orbits its star at a distance reminiscent of Mars' path around the Sun — close enough to hint at habitability, far enough to avoid scorching. Researchers call it "where Earth meets Mars," a cosmic crossroads between the familiar and the unknown.

"This is the kind of exoplanet that makes your heart race," says UniSQ researcher Chelsea Huang. "For 30 years, astronomers have hunted for Earth's twin. HD 137010 b isn't the twin yet, but it's the closest we've come."

The planet's allure is its potential habitability. Lead author Alex Venner estimates there's a 50 percent chance liquid water could exist there — the holy grail for life as we know it. But there's a catch: we have no way to measure its atmosphere yet. It could be a temperate haven… or a frozen wasteland plunging to minus 70 degrees Celsius. Science is holding its breath.

And the story behind its discovery is straight out of a cosmic detective tale. HD 137010 b first emerged from the work of Planet Hunters, an online citizen science project. Volunteers scoured NASA's Kepler mission data, spotting tiny dips in starlight — the faint "winks" of a planet passing in front of its star. One of those volunteers was a teenage Alex Venner in Wales. Years later, as a PhD researcher at UniSQ, he returned to the data and realized something extraordinary: one of those winks could be an Earth-sized world hiding in plain sight.

After years of calculations, simulations, and collaboration, the candidate planet earned its place in the Astrophysical Journal Letters — and caught NASA's attention. Yet the excitement is tempered by caution. NASA scientist Dr Jessie Christiansen calls it "incredibly tantalising… but almost heartbreaking," since only a single transit has been observed. One more transit, and HD 137010 b could become the only confirmed rocky planet in the habitable zone of a Sun-like star. That would be historic.

Even then, researchers warn against premature celebration. UniSQ professor Jonti Horner reminds us that "potentially habitable" does not guarantee life — Venus and Mars share our Sun's habitable zone, but only Earth truly thrives. Still, he calls HD 137010 b a "tantalising sneak peek" of what's out there, the kind of planet every astronomer dreams of finding.

HD 137010 b is a whisper from the cosmos, a hint that somewhere in the darkness, worlds like ours might exist. Whether it turns out to be a twin of Earth or a frozen stranger, it reignites the age-old question that keeps astronomers looking skyward: are we alone, or is the galaxy teeming with possibilities?

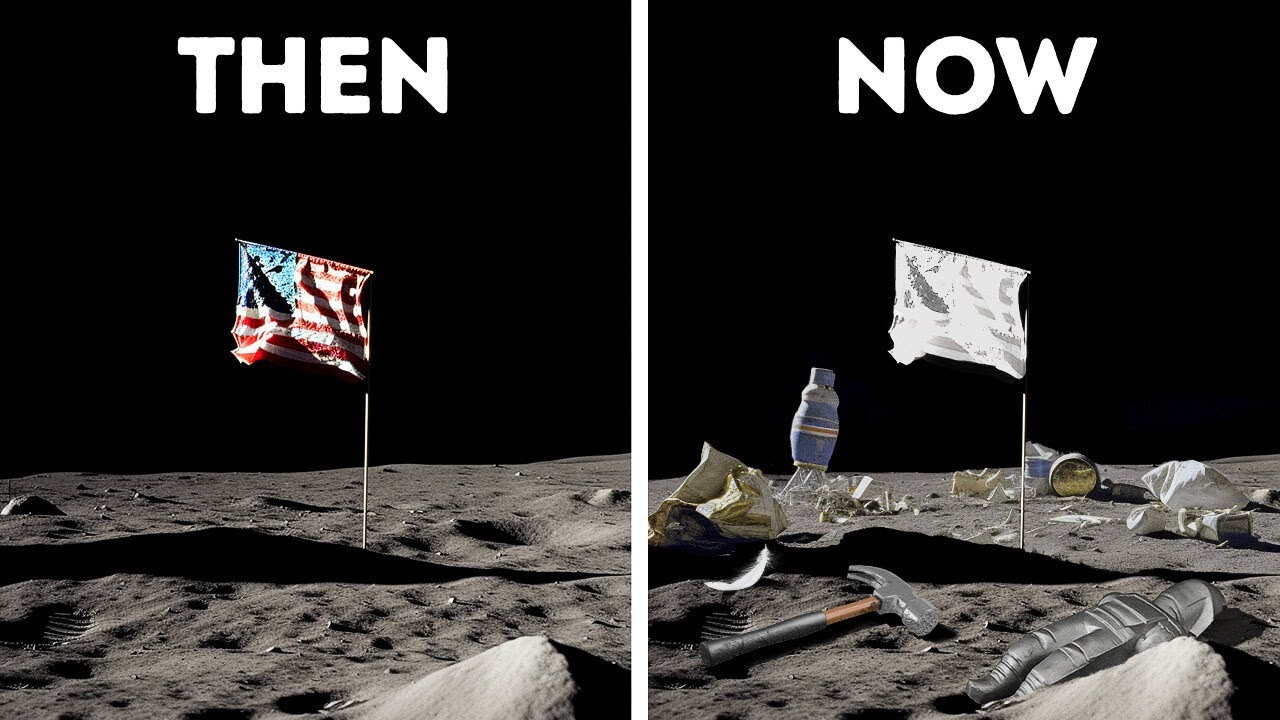

What Happened to the Flags Left on the Moon?

On the Moon, nothing ages quietly. When the Apollo astronauts planted their flags between 1969 and 1972, they were not thinking about preservation. The flags were symbols, gestures, moments frozen for television and history books. Lightweight, practical, and never designed to last forever, they were made of ordinary nylon—chosen not for endurance, but for weight. On Earth, nylon can survive years. On the Moon, it is left naked before one of the harshest environments imaginable.

There is no air on the Moon. No clouds. No protective atmosphere. No ozone layer to soften the Sun's glare. From the moment the astronauts departed, the flags were exposed to relentless ultraviolet radiation. UV light is brutal to dyes, especially the red and blue pigments that give the American flag its colour. Over decades, that radiation would steadily break down the molecular bonds in the fabric. The result would not be a proud red, white, and blue banner fluttering heroically, but something ghostly—washed out, pale, perhaps almost white. Ironically, the white stripes may now be the most recognisable feature left.

The Sun is not the only enemy. The Moon experiences temperature extremes that defy everyday intuition. During lunar daytime, the surface can reach about 120 degrees Celsius. At night, it can plunge to around minus 170. These swings happen every lunar day—roughly every 29 and a half Earth days—over and over again, for more than half a century. Nylon does not cope well with repeated expansion and contraction at those extremes. The cloth would gradually become brittle, losing flexibility, turning stiff and fragile, like plastic left too long in the Sun.

Then there are micrometeorites. The Moon has no atmosphere to burn them up. Tiny grains of cosmic debris strike the surface constantly at enormous speeds. Individually, they are insignificant. Over decades, they are relentless. Each impact is a microscopic sandblasting event. The flags would have been peppered again and again, the fibres slowly eroded, the weave weakened, the edges frayed beyond recognition. And yet, the poles themselves may still be standing.

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has photographed the Apollo landing sites, and in several cases, shadows consistent with upright flagpoles can still be seen. The flags, however, are too small and too altered to be resolved directly. If the cloth remains attached at all, it may hang in tatters—or may have disintegrated entirely, leaving only a pole casting a thin, stubborn shadow across the lunar dust.

One flag may already be gone. Buzz Aldrin later recalled that the Apollo 11 flag was likely blown over by the exhaust of the lunar module as it lifted off. The others were planted farther away, safer from the blast, but still helpless against time.

There is something quietly poetic about this. On Earth, monuments are weathered by wind and rain. On the Moon, history is erased by sunlight and silence. The flags are not preserved by the vacuum of space; they are punished by it. And yet, their fading does not diminish their meaning. If anything, it sharpens it.

These flags were never meant to be permanent. They were not claims of ownership, nor declarations meant to endure forever. They were markers of a moment when humans, fragile and brief as nylon fabric, stepped beyond their home world and touched another. The fact that the colours have likely vanished only underscores how extraordinary that moment was. Human presence was fleeting. The achievement was not.

Somewhere on the Moon, under an unfiltered Sun, a brittle remnant may still cling to a metal pole, bleached nearly white, unmoving in a sky that never turns blue. No wind stirs it. No eye watches it. And yet it stands as one of the quietest monuments ever made—not a flag waving in triumph, but a silent reminder that humanity once reached across 384,000 kilometres of space and left something behind, even if time itself is slowly erasing the colours.

'Point Nemo ' - Where Is The Designated Space Graveyard?

There is a place on Earth so remote, so deliberately avoided, that it has quietly become the final resting place for humanity's greatest machines. It's not marked on maps with warning signs. No ships pass through it. No aircraft fly overhead unless they absolutely have to. This is the Space Graveyard — a vast patch of the southern Pacific Ocean officially known as Point Nemo.

The idea of a controlled spacecraft graveyard emerged during the early decades of the Space Age, once engineers realised that satellites and stations couldn't simply be abandoned forever. By the 1970s, space agencies had begun deliberately targeting Point Nemo for re-entries, because it is the farthest point on Earth from any landmass — more than 2,600 kilometres from the nearest island. If something large had to come down, this was the safest place to aim.

And quite a lot is already down there. More than 260 spacecraft have been intentionally deorbited into this region, including Soviet-era space stations, defunct cargo vehicles, and experimental hardware. Most of it never made it past the atmosphere, burning up in spectacular but unseen fireballs. What survived — heat-resistant tanks, dense structural pieces — now lies scattered across the ocean floor several kilometres below the surface, in total darkness, slowly rusting in silence. It is, quite literally, the world's most unreachable museum.

And one day, the largest object humans have ever built in space will join it. The International Space Station is humanity's longest-running house party in orbit — and like all great gatherings, one day the music has to stop.

Launched piece by piece beginning in 1998, the ISS has been continuously occupied since November 2000, when NASA astronaut Bill Shepherd and Russian cosmonauts Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev floated aboard and switched the lights on. Since then, not a single day has passed without humans living above Earth, circling the planet every 90 minutes at 28,000 kilometres an hour. That's more than two decades of sunrises and sunsets — about 16 a day — seen through a window the size of a microwave oven.

Over those years, the ISS has quietly earned its keep. It has helped sharpen weather forecasting, advanced medical research into muscle loss and bone density, tested new materials, improved crop science, and acted as a dress rehearsal for long-duration missions to the Moon and Mars. It's been part laboratory, part observatory, part gym, part international peace project — and occasionally, part space junk drawer, with lost tools drifting past like cosmic socks. But even legends age.

Under current plans, the ISS will reach the respectable space age of 32 in 2030. At that point, it won't be abandoned to drift forever like a ghost ship. Instead, engineers will guide it to a controlled, dramatic finale — a carefully choreographed fall back to Earth. The destination is Point Nemo, the most remote location on the planet.

Getting a 463-ton space station down is no small trick. First, its orbit will be gradually lowered using propulsion and Earth's upper atmosphere, which, thin as it is, still tugs at objects like an invisible handbrake. Once the final crew has returned safely home, controllers will commit the ISS to its last journey. A powerful re-entry burn will send it plunging into the atmosphere. Much of it will burn up in a spectacular, unseen fireball. The tougher pieces will survive the inferno and splash into the Pacific, joining the scattered remains of other retired spacecraft.

The entire operation will be managed jointly by NASA, the Canadian Space Agency, the European Space Agency, Japan's JAXA, and Russia's Roscosmos — the same five partners who built, maintained, argued over, and ultimately kept the station alive for more than three decades. It's a rare thing in human history: a truly global machine, ending its life exactly as it lived it — cooperatively.

After the ISS is gone, NASA won't be leaving low Earth orbit behind. Instead, it plans to hand the keys to private companies, transitioning to commercially owned space stations while focusing government efforts on deeper space. In other words, the ISS is retiring so the next generation of orbital outposts can clock in. And then there's Point Nemo itself.

Despite what Pixar may have implanted in our collective brains, the name doesn't come from a forgetful clownfish. It traces back to Captain Nemo, the brooding, brilliant mariner from Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Fittingly, nemo also means "no one" in Latin — and Point Nemo truly belongs to no one. It lies farther from land than anywhere else on Earth, so isolated that the closest humans are often astronauts passing overhead. Which makes it strangely perfect.

After a lifetime spent circling the planet, watching wars, auroras, storms, and city lights glide silently beneath it, the ISS will make its final descent to the loneliest place on Earth. No crowds. No monuments. Just one last plunge — and a quiet resting place at the bottom of the world. Not a bad way to go out for a machine that spent its life above us all.

This startup will send 1,000 people's ashes to space — affordably — in 2027

Ryan Mitchell was lying under the stars at a state park when a question quietly formed: what comes next? He wasn't a dreamer without credentials. Mitchell is a manufacturing engineer who worked on NASA's space shuttle program before spending nearly a decade at Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos' space company. During those years, he watched the cost of reaching space fall dramatically. Thanks largely to SpaceX, orbit no longer felt unreachable. That night, the stars seemed closer than ever.

The idea took shape later, during a family member's ash-spreading ceremony. When it ended, Mitchell felt something unresolved. "There was this sense of 'now what?'" he recalled. "The moment was gone." He couldn't shake the thought: how could this be done better?

That question became the foundation of Space Beyond, his startup, and its "Ashes to Space" program. The concept is simple but striking: send a small portion of people's ashes into orbit. Space Beyond plans to use a CubeSat — a miniature cube-shaped satellite — capable of carrying the ashes of up to 1,000 people at once.

In October 2027, that CubeSat is scheduled to launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rideshare mission, following a launch services agreement with Arrow Science and Technology. Memorial spaceflights themselves are not new. Companies like Celestis have offered them since the 1990s. What makes Space Beyond different is price.

Its cheapest option starts at $249, compared with the thousands typically charged elsewhere. Families arrange cremation separately, but the spaceflight is designed to be accessible. Mitchell credits this to the rideshare model, where small CubeSats hitch a lift aboard larger missions for a fraction of the cost, opening space to science experiments, startups — and now memorials.

Space Beyond is also fully bootstrapped. Mitchell isn't chasing venture capital or massive returns. "I've been told I'm not charging enough," he said, especially in an industry known for over-charging people during moments of grief. "But I'm not trying to take over the world. I'm not trying to make a billion dollars."

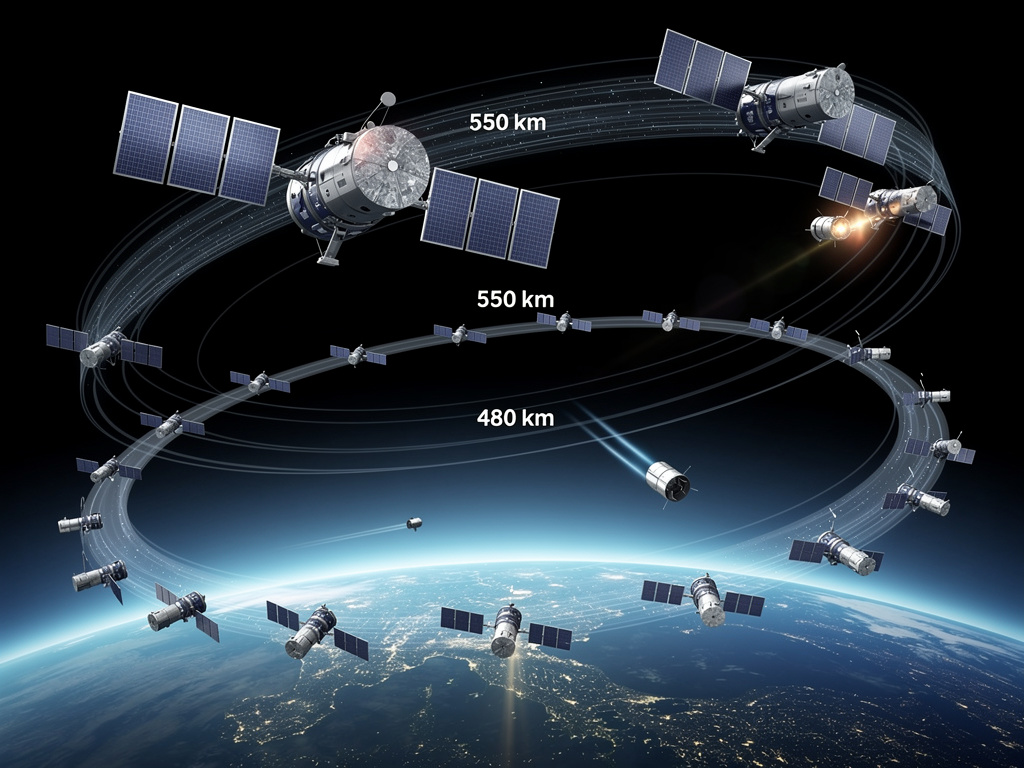

There are limits. Each customer can send only about one gram of ashes, a practical necessity when mass still matters in spaceflight. The CubeSat will remain in orbit for about five years, meaning this is not a permanent memorial.

Mitchell sees meaning in those constraints. The satellite will fly in a sun-synchronous orbit, roughly 550 kilometres above Earth, passing over nearly every point on the globe. With modern satellite-tracking tools, families will be able to know when that small spacecraft — carrying part of a loved one — is moving through their night sky.

After about five years, the CubeSat will re-enter Earth's atmosphere and burn up completely. The aluminum structure and the ashes inside will meet a fiery end high above the planet — a symbolic final release, even if there's no guarantee anyone will witness the fireball.

What Space Beyond will never do is scatter ashes in space. That would be dangerous, Mitchell explains. Loose particles could become orbital debris, threatening other spacecraft. Instead, ashes remain sealed, while families are free to decide what to do with the remainder on Earth.

When Mitchell left Blue Origin last year, he filled pages of a notebook with ideas for what might come next — from taking another role in the space industry to becoming a kava bartender. Yet this idea kept resurfacing.

"I tried to talk myself out of it," he said. It seemed too expensive, too complex. But each time he applied engineering rigor — the physics, the requirements, the business case — it held together. It was also the idea he couldn't stop talking about.

"My wife said, 'I could have told you weeks ago,'" he laughed. "'You're obsessed with this.'" And so, from a quiet night under the stars to a CubeSat bound for orbit, Space Beyond emerged — offering a new way to say goodbye, written not in stone, but across the sky.

Out Of The Twelve Humans Who Have Ever Set Foot On The Moon Only Four Are Still Alive Today!

Buzz Aldrin. David Scott. Charles Duke. Harrison "Jack" Schmitt. Four names. Four voices. Four living links to one of the most extraordinary chapters in human history. When they speak, they do not describe a dream or a theory. They describe a place they have stood, a world they have touched.

Between 1969 and 1972, NASA's Apollo program carried humanity farther than it had ever gone before. In just eight short missions that reached the lunar surface, humans crossed the vast emptiness between Earth and Moon, landed on an alien world, and returned safely. It remains, more than half a century later, the greatest physical journey our species has ever achieved.

The Apollo era unfolded at breathtaking speed. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy challenged the United States to land a man on the Moon before the decade was out. At the time, America had barely managed short orbital flights. Rockets failed. Astronauts died in training accidents. Computers filled rooms and were less powerful than a modern calculator. Yet less than eight years later, Apollo 11 touched down in the Sea of Tranquility.

Buzz Aldrin stepped onto the lunar surface just minutes after Neil Armstrong, becoming the second human to walk on another world. He described the Moon not as poetic fantasy, but as stark reality: harsh sunlight, absolute silence, and a horizon so close it felt unreal. Aldrin's footprints are still there today, sharp and undisturbed, because the Moon has no wind, no rain, and no erosion. They are, in a literal sense, history frozen in time.

Apollo did not stop there. The early missions proved landing was possible. The later ones turned exploration into science. David Scott, commander of Apollo 15, led the first mission designed for extended stays on the Moon. His crew drove the lunar rover across valleys and mountain slopes, covering distances once thought impossible. Scott famously dropped a hammer and a feather on the Moon to demonstrate Galileo's principle that, without air resistance, all objects fall at the same rate. It was a quiet moment, but one that connected ancient science to the modern age, played out on another world.

Charles Duke, the youngest of all Moonwalkers, landed with Apollo 16. He bounded across the lunar highlands, collecting rocks that revealed the Moon's violent past. Duke later spoke openly about the emotional toll of the space race, describing how fame arrived suddenly, and how returning to ordinary life on Earth was often harder than walking on the Moon itself. His experience reminds us that these explorers were not mythic figures, but human beings carrying immense pressure on their shoulders.

Harrison Schmitt stands apart from the others in a unique way. Apollo 17's lunar module pilot was the only professional geologist ever to walk on the Moon. While others were trained to become scientists, Schmitt already was one. His sharp eye led to the discovery of orange volcanic soil, proof that the Moon once experienced fire and fury, not just cold silence. When Schmitt and commander Eugene Cernan left the Moon in December 1972, no one knew it would be the last time humans would stand there. Cernan's final words on the lunar surface were a promise that humanity would return. So far, that promise remains unfulfilled.

That fact alone makes the four surviving Moonwalkers even more extraordinary. More than fifty years have passed since Apollo ended. Entire generations have been born, grown old, and passed away without a single human returning to the Moon. Space stations circle Earth. Robots roam Mars. Telescopes peer to the edge of the universe. Yet the most distant footsteps humans have ever taken remain those dusty prints left between 1969 and 1972.

These men are not just veterans of a program. They are living evidence of what humans can do when curiosity outruns fear, and determination overpowers doubt. They remind us that the Moon was not reached by accident or luck, but by vision, teamwork, and relentless effort. Hundreds of thousands of people worked behind the scenes so that a dozen could walk on another world.

As the years pass, their voices grow rarer, and their presence more precious. When Buzz Aldrin, David Scott, Charles Duke, and Harrison Schmitt speak, they do not talk about what might be possible someday. They talk about what was already done.

They are the last living witnesses to humanity's boldest leap into the unknown. And until humans return to the Moon, they remain our closest connection to the moment when Earth became, for the first time, something we could look back upon from another world.

Artemis II Crew Enters Quarantine Ahead of Journey Around the Moon

In a milestone that bridges half a century of silence beyond low Earth orbit and humanity's return to deep space, the four astronauts selected for NASA's Artemis II mission have entered quarantine as their final preparation phase ahead of an historic lunar flyby.

On January 23, 2026, NASA confirmed that the Artemis II crew — Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, Mission Specialist Christina Koch, and Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen — began strict isolation at NASA facilities in Houston. This medical quarantine isn't about drama, it's about ensuring peak health for a flight that could take them farther from Earth than any humans since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Quarantine protocols require astronauts to limit contact with others, wear masks in shared spaces, and avoid public places in the weeks leading up to launch. The goal is simple: reduce every avoidable risk of illness that could delay or compromise a mission into deep space.

Countdown to History

While no official launch date has yet been certified, mission planners are eyeing opportunities beginning in early February 2026. As long as technical tests and spacecraft readiness checks proceed smoothly, the crew will travel to NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida about six days before liftoff, where they'll continue final preparations at the Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building.

Ground teams are also hard at work. Engineers have completed key preparations on the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the Orion spacecraft, including power system checks, cryogenic plumbing evaluations, and engine inspections at Launch Pad 39B.

Above all this work on Earth, additional teams — including personnel from NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense — are rehearsing post-splashdown recovery procedures at sea, ready to collect the crew when the mission concludes in the Pacific Ocean.

What Makes Artemis II Different

Artemis II will mark the first crewed flight of NASA's modern deep-space exploration architecture, flying humans around the Moon and back aboard the Orion spacecraft. It's an approximately 10-day mission that will test spacecraft systems in deep space conditions and demonstrate readiness for future lunar surface missions like Artemis III.

This mission isn't just about a ride around the Moon — it's a test by fire. The crew will be exposed to radiation environments far harsher than those encountered in low Earth orbit, and will operate life-support and navigation systems that are the first of their kind for human spaceflight.

Faces of the New Lunar Era

The Artemis II crew embodies a diversity of experience and national partnership. All four are seasoned explorers and scientists in their own rights, with flights aboard the International Space Station (ISS) among their credentials. The inclusion of Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen underscores growing international collaboration in deep-space exploration.

At the heart of the mission is the Orion spacecraft, affectionately named "Integrity" by the crew — a symbolic reminder of the principles guiding modern space exploration.

A Mission With Broader Horizons